Think like a go player!

Terminology of the ancient Chinese game has found its way into everyday communication

Hideyuki Fujisawa, a master of the ancient Chinese game of Go, once remarked that if there were 100 ways of playing the game, he knew only about seven.

Humility aside, the recent defeat of world champions Lee Sedol and Ke Jie by the computer program AlphaGo has arguably proved Fujisawa's point.

"I only know about 2 percent ... mankind's knowledge of Go is far too limited," Ke conceded at a news conference in May.

The ancient Chinese viewed Go with awe. Faced with its infinite possibilities and abstract thinking, pushing the limits of the human mind, they coped by mystifying the game. A description of Go's invention in The Comprehensive Mirror of Immortals in History, an 18th-century collection of legends, states: "The chess board is square and still, while the Go pieces are round and mobile. They represent the Earth and Heaven. Since the invention of the game, there's none who can figure out a universal solution."

According to the book, the legendary emperor Yao was seeking to teach his dim but aggressive son a lesson. He met two immortals by a river, who suggested using Go, 圍棋 (wéi qí, lit. "encircling chess").

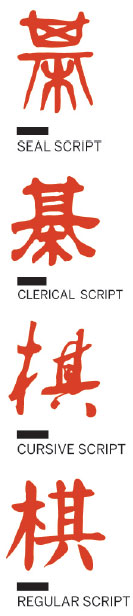

棋 (qí, chess) alone can refer to any type of chess - 象棋 (xiàngqí, Chinese chess), or 國際象棋 (guójì xiàngqí, lit. "international chess," the kind with bishops and queens). Go's English name came from the Japanese pronunciation of the character, a variant of 棋 (qí) in Chinese. The former makes more sense referring to Go, given the stone radical, 石 (shí), at the bottom of the character, since Go pieces were often made of stone.

Traditionally, 弈 (yì) was the Chinese character referring specifically to Go. Although 圍棋 is used in most discourse, 弈 is still found in a series of phrases related to Go: For instance, playing chess can be 下棋 (xià qí) or 對弈 (duìyì). The term 博弈 (bóyì), originally referring to playing Go, could also mean "to gamble," while game theory in modern mathematics is translated as 博弈論 (bóyìlùn). In this sense, 博弈 refers to the act of two or more opposing parties utilizing certain strategies to gain advantage or profit.

A major form of entertainment in ancient China, Go has left linguistic traces in many phrases and idioms. Those having difficulty making up their mind are often said to be 舉棋不定 (jǔqíbùdìng, lit. "holding a Go stone, but unsure where to put it), the implication being that one must not allow doubt and hesitation to interfere with one's goals.

It is said that a bad Go player only focuses on picking off an opponent's pieces from the board, while a good player seeks superior advantage with a long-term strategy. In such circumstances, every turn could be a matter of life or death. One false move could see the loss of the whole game, or 棋錯一著, 滿盤皆輸 (qí cuò yīzhe, mǎn pán jiē shū) - a truth that could be applied to any endeavor.

Any competition can be described like a game of Go: One may meet one's match, 棋逢對手 (qíféngduìshǒu, lit." to encounter an equal opponent at Go"), or encounter a stronger opponent, 棋高一著 (qí gāo yīzhe, lit. "an opponent who is a notch above you at Go").

Since Go often involves complicated strategies, a game is referred to as a 棋局 (qíjú, lit. "a situation confronting players in a chess game"). Overly focused players may turn a blind eye to what's hidden in plain sight, a phenomenon called 當局者迷, 旁觀者清 (dāngjúzhěmí, pángguānzhěqīng), which translates as "spectators see the game better than the players".

Yet while a player in the midst of making moves may miss the bigger picture, it could also be argued that those who are directly involved know the game better. That is why spectators are referred to as 局外人 (júwàirén, lit. "people outside the context"), a term that also refers to outsiders in general - it's the Chinese title of Camus' The Stranger.

Go terminology has even managed to find its way into everyday communication. A game is divided into three stages, 布局 (bùjú, opening moves), 中盤 (zhōngpán, midgame) and 官子 (guān zi, final stage). 布局 can also mean any kind of arrangement, layout or composition, while 官子 or the verb 收官 (shōu guān) is also used to refer to the final stage of any large project. For instance, the fifth year of a government five-year plan is always referred to as 收官之年 (zhōu guān zhī nián, a final-stage year).

From mystic origins to modernday politics, Go is not just a game - it's a whole way of thinking.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com.cn

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 08/11/2017 page23)

Today's Top News

- Digital countryside fueling reverse urbanization

- 'Sky Eye' helps unlock mysteries of the universe

- China offers LAC development dividend

- Future sectors to receive more play

- Nation sets its sights on export boost

- China to open its door to foreign investment wider