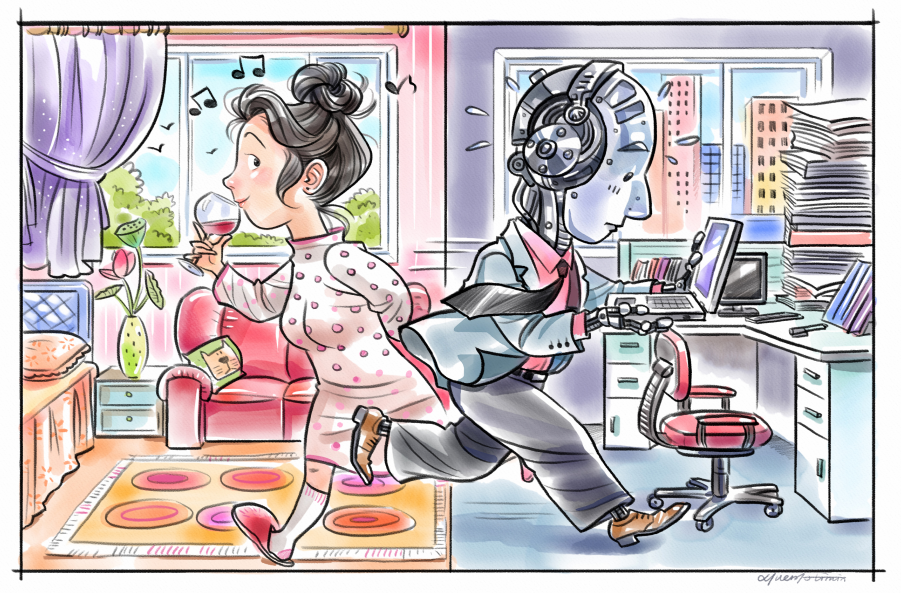

In the future, how an AI utopia would work

It is more than 500 years since Sir Thomas More found inspiration for the "Kingdom of Utopia" while taking a stroll on the streets of Antwerp, Belgium. So, when I traveled there from Dubai in May to speak about artificial intelligence (AI), I couldn't help but draw parallels to Raphael Hythloday, the character in Utopia who regales sixteenth-century Britons with tales of a better world.

As home to the world's first Minister of AI, as well as museums, academics and foundations dedicated to studying the future, Dubai is on its own Hythloday-esque voyage. While Europe, in general, has grown increasingly anxious about technological threats to employment, the United Arab Emirates has enthusiastically embraced the labor-saving potential of AI and automation.

There are practical reasons for this. The ratio of indigenous-to-foreign labor in the Gulf states is highly imbalanced, ranging from a high of 67 percent in Saudi Arabia to a low of 11 percent in the UAE. And because the region's desert environment cannot support further population growth, the prospect of replacing people with machines has become increasingly attractive.

But there is also a deeper cultural difference between the two regions. Unlike Western Europe, the birthplace of both the Industrial Revolution and the "Protestant work ethic", Arab societies generally place a greater value on leisure time.

In the industrialized West, technological forces threaten social contracts that have long rested on the three pillars of capital, labor and the state. For centuries, capital provided investment in machines, workers operated the machines to produce goods and services, and governments collected taxes, furnished public goods, and redistributed resources as needed. But this division of labor created a social system that is far more complicated than those of the Arab world and other non-industrialized economies.

For their part, Arab states have nationalized natural resources, managed major industries and traded internationally. Until recently, population growth and declining revenues from natural resources threatened the social contract. But with technologies that can produce and distribute most of the goods and services required by what is essentially a leisure society, the existing social contract could actually be enhanced, rather than disrupted.

In the West, the technological revolution appears to have widened the gap between capital owners and everyone else. While productivity has been increasing, labor's share of total income has shrunk. Apart from the capital owners, a leisure class of yuppies and heirs has also captured a sizable share of the surplus created by productivity-enhancing technologies. The biggest losers are those with low incomes and less education.

Yet, even here, focusing on AI's potential impact on the relationship between capital and employment is shortsighted. After all, populism has surged in many Western countries at a time of near-historic lows in unemployment. Arguably, the current discontent reflects a desire for a better quality of life, not more work.

The French "yellow vest" protesters were initially responding to policies that would have raised the costs of their commutes; Britons who voted to leave the European Union were hoping that contributions to the bloc would be redirected to public services at home. Most anti-globalization and anti-immigration rhetoric is born of an anxiety about crime, cultural change and other quality-of-life issues, not jobs.

The problem is that, under the Western social contract, a desire for more leisure can translate into mutually incompatible demands. Voters want reduced working hours but higher incomes, and they expect governments to continue generating enough tax revenue to provide healthcare, pensions and education. No wonder Western politics has reached an impasse.

Fortunately, AI and data-driven innovation could offer a way forward. In what could be perceived as a kind of AI utopia, the paradox of a bigger state with a smaller budget could be reconciled, because the government would have the tools to expand public goods and services at a very small cost.

The biggest hurdle would be cultural: As early as 1948, German philosopher Joseph Pieper warned against the "proletarianization" of people and called for leisure to be the basis for culture. Westerners would have to abandon their obsession with the work ethic, as well as their deep-seated resentment toward "free riders". They would have to start differentiating between work that is necessary for a dignified existence, and work that is geared toward amassing wealth and achieving status. The former could potentially be all but eliminated.

With the right mindset, all societies could start to forge a new AI-driven social contract, wherein the state would capture a larger share of the return on assets, and distribute the surplus generated by AI and automation to residents. Publicly owned machines would produce a wide range of goods and services, from generic drugs, food, clothes and housing, to basic research, security and transportation.

Some will view these outlays as unjustified market intervention; others will worry that the government might fail to meet public demand for various goods and services. But, again, such arguments are shortsighted. Given the pace of advances in AI and automation, state-owned production systems-operating nonstop-will have an almost unlimited supply capacity. The only limitation will be natural resources, a constraint that would continue to drive technological innovation in search of more sustainable management.

In an AI utopia, government intervention would be the norm, and private production the exception. The private sector would correct government or collective failures, rather than the government correcting for market failures.

Imagine traveling forward in time to 2071, the UAE's centenary. A future Raphael Hythloday visiting Antwerp from Dubai would bear the following news: Where I live, the government owns and operates the machines that produce most necessary goods and services, allowing the people to spend their time on leisure, creative and spiritual pursuits. All worries about employment and tax rates have been consigned to the past. That could be your world, too.

The author is director of Strategy and Research at the Dubai Future Foundation and a non-resident fellow at The Lisbon Council. He is the author of Black Swan Start-ups: Understanding the Rise of Successful Technology Business in Unlikely Places.

Project Syndicate

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.