Revealing their true colors

Family's decadeslong mastery of dyeing technique continues, Yang Feiyue reports.

A bluish backdrop with white shapes could conjure images of clouds and sky, or even of undulating oceans, but under Wang Zhenxing's skillful ministrations, it can also become a delicate piece of fabric art.

In his deft fingers, the intricate white patterns emerging on the blue fabric, which range from the floral and the geometric to the whimsical, have a way of drawing those that look at them into the world of Chinese tradition and tranquillity.

"If you get closer to the cloth, you'll notice a faint fragrance. This is the scent of indigo mixed with soybean and lime powder paste," says Wang, who's in his 80s.

The concoction has insect-repelling, anti-inflammatory and detoxifying effects, the artisan from Nantong in Jiangsu province adds.

For the past six decades, Wang has been practicing blue calico printing and dyeing, one of the first crafts named as a form of national intangible cultural heritage in 2006.

"The background is neither pure white, nor pure blue, but a blend of both, and resembles an ink-wash painting — that is what truly defines blue calico printing and dyeing," Wang says as he explains the distinctive, subtle beauty of the craft, which has occupied a spot in the media limelight since influential content creator Li Ziqi visited him in 2018 to learn his secrets.

After she posted a video demonstration in 2020, online searches spiked on social media platforms like Douyin and Sina Weibo.

When Li came to see Wang again in March, she was excited to discover that his sons and grandchildren have also turned their hand to the craft, and spoke about how some of the dyed products Wang showed her were more fashionable, and in line with the taste of young people.

The Chinese use of indigo, a dye made from bluegrass, can be traced back to the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770-221 BC), when the philosopher Xunzi spoke about watching green bluegrass dye turning from yellow to green, from green to blue, and finally to cyan.

The cotton fabric was deeply loved for its colorfast, rustic properties, especially in coastal areas where it rains a lot, like it does in Jiangsu.

With the development of the cotton textile industry in Nantong during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the use of indigo with cotton textiles expanded.

Thanks to a warm and humid local climate, bluegrass was cultivated extensively, and dye workshops multiplied.

According to records, there were as many as 19 hand-dyeing workshops registered with the dyeing and weaving bureau during the period, when indigo products were one of the main tributes submitted to the imperial court.

Nantong blue calico is entirely made by hand, from the spinning and weaving to the dyeing. The patterns are also handmade, using engraved paper stencils that resemble the art of paper-cutting. The style is simple and rugged, and the imagery is often abstract and exaggerated, according to cultural experts.

The patterns are typically a combination of a frame with central motifs. Most are symbolic, conveying auspicious meanings, and images of flowers, birds, fish and insects often serve as carriers of meaning.

Ever since he became an apprentice at a local dye plant at the age of 18, Wang has followed through on his commitment to the art, continuing to practice techniques dating to the Ming Dynasty.

The bluegrass is first soaked in a stone tank, and after a few days, its decaying remains are removed. Lime is added to make the mixture settle and the resulting sediment-like dye is called earth indigo.

Then comes the carving of the pattern plate. Laminated or kraft paper is soaked in tung oil, dried and cut into the desired size for the plate, before the pattern is carved.

Paste made out of soybean flour and lime powder mixed with water is plastered across the plate. The pattern is then printed onto cloth, which is placed underneath the plate.

"You can't stop and start again; the carving needs to be done in one continuous movement to ensure smooth lines and an ethereal feel, which requires proficiency," Wang says.

Each time the paste is applied, force must be even, the alignment precise and the pattern placement smooth, he adds.

Then dyeing begins.

The fabric is removed from the plate and placed in clean water until it is soaked and the paste softens. It is then submerged in a dye tank for about 20 minutes, and left to dry in the air for 30 minutes to allow the indigo to oxidize. As this happens, the fabric is turned frequently to ensure even exposure to the air.

"The dipping and oxidizing process has to be repeated six to eight times, depending on the material and weather conditions," Wang says.

After dyeing, the fabric is dried and treated with an acid solution to fix the color, before being washed and stretched on a frame. The remaining paste is scraped off using a delicate knife.

The fabric undergoes a second acid-fixing and is washed two to three times to create a clear contrast between the blue and white areas.

"Each step of the process is quite intricate, so it's a task that truly tests one's patience and attention to detail," Wang says.

But the reward is worthwhile, as no two pieces are ever identical, giving each piece a unique personality and life.

To help preserve the craft, Wang has roped his entire family into the trade. His youngest son, Wang Jianwei, 50, has mastered the techniques of indigo tank preparation; his second son, Wang Jianyong, 56, has taken charge of dyeing, paste preparation, and pattern application; and his eldest son, Wang Jianfeng, 57, handles the making of the templates. Even his granddaughter, who was born in the 2000s, has taken on pattern and product design.

Wang Jianyong, who has watched his father since he was a child, has decided to take up the family mantle.

He says that the transition from white cotton fabric to meticulously designed patterns in different hues of blue is like magic.

"It's like watching a child grow from babbling to maturity," he says, adding that the resulting sense of pride comes straight from the heart.

While upholding traditional techniques, the family members have also left their own stamp on the craft, and produced three shades of blue — dark, medium and light — and made use of a variety of techniques, including traditional Chinese painting, woodblock printing, and folk paper-cutting.

Wang Zhenxing and his family have also developed new products like backpacks, makeup bags, home decorations and hair accessories, and despite his years, he continues to work at the family dye house, promoting blue calico art.

Since their facility was named a national intangible cultural heritage protection base in 2006, visitors have come from across the country. It has received students from more than 100 institutes of higher learning, and international visitors from Japan, South Korea and Russia have also come to appreciate the art.

Wang Jianfeng still vividly remembers Li Ziqi's visit.

"She is clearly very into the inheritance and development of blue calico printing and dyeing," he says. "Thanks to her, more people have come to know the art, and we hope more will come."

Today's Top News

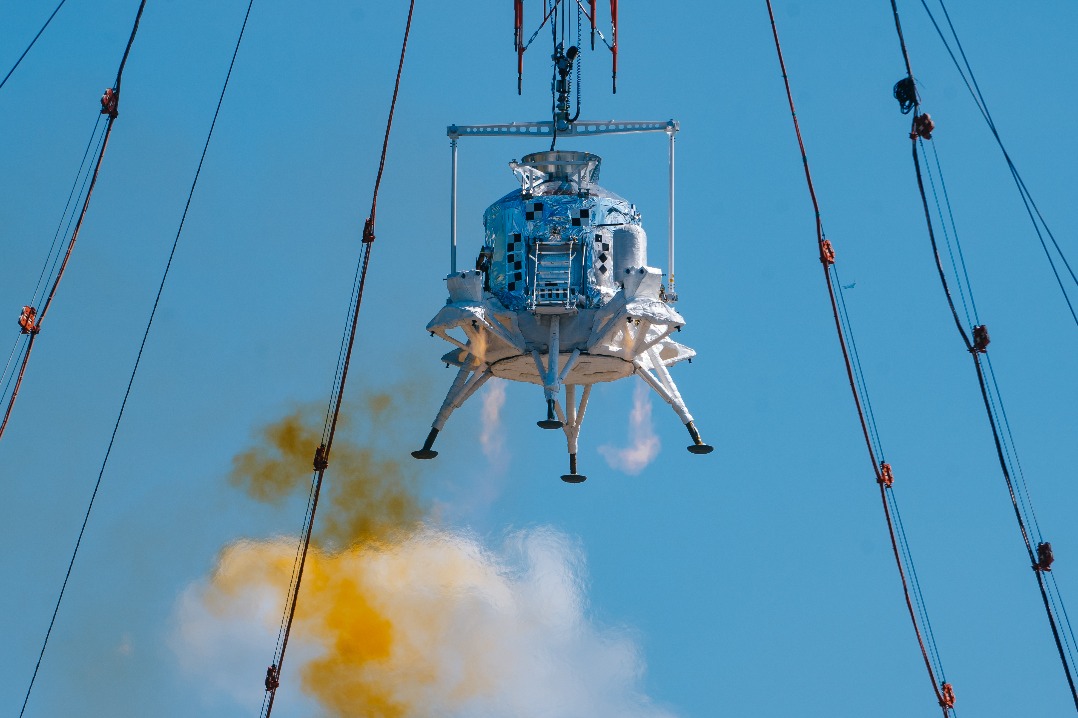

- China completes first landing, takeoff test of manned lunar lander

- China's new free preschool policy to save families $2.8 billion

- China's foreign trade rises 3.5% in first seven months

- China's foreign trade up 3.5% in first seven months

- 25-yuan roast duck reflects progress of rural vitalization

- Xi set stage for rise of cultural powerhouse