A remedy from history

Writing about the rediscovery of ancient antimalarial treatment, author poses thought-provoking questions, Yang Yang reports.

In 330, Ge Hong, a Taoist scholar and alchemist born in 283, moved to Luofu Mountain in present-day South China's Guangdong province to continue his pursuit of physical immortality, which he believed could be attained through alchemy.

He soon became known for his lifesaving prescriptions. Apart from alchemy, Ge spent much of his time studying herbal medicine and collecting and testing different prescriptions before recording his findings in books like the Zhou Hou Jiu Zu Fang (later known as the Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang), a prescription guide for emergencies.

One day, a farmer from a village at the foot of the mountain came to seek Ge's help. Many of the villagers had fallen ill, suffering from alternating chills and fever. Some had even died. It was a common affliction in the south of China, and was thought to be caused by miasmas. Ge gave the farmer two different prescriptions, and told him that they might take effect three days after drinking them.

Three days later, Ge's student reported that both prescriptions had worked, so he noted them down in the Zhou Hou Jiu Zu Fang.

In the late 19th century, more than 1,500 years later, the cause of the disease was finally discovered. The alternating chills and fever were brought on by malaria, a disease that is estimated to have killed between 25 and 50 percent of all humans that have ever lived.

By way of treatment for malaria, Ge recorded 43 prescriptions in the Zhou Hou Jiu Zu Fang, including the two he gave to the farmer — one based on changshan, or dichroa root, an antifebrile, and another based on qinghao, or sweet wormwood.

"Take a handful of qinghao, soak it in two sheng (about 400 millimeters) of water, squeeze out the juice, and consume all of it," Ge writes.

It was not until the latter half of 1971, when pharmaceutical chemist Tu Youyou was rereading the Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang as part of her research into effective traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions to treat malaria, that qinghao emerged as a promising choice.

Tu explained when she received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2015 that, the research team of which she was a member had tried the plant, but its effect proved unstable. When Tu read Ge's prescription, it suddenly occurred to her that the extraction process might need to avoid high temperatures, and so she considered using a method that involved solvents with lower boiling points.

This unusual spark led to a groundbreaking scientific discovery, resulting in a new drug that has saved millions of lives and benefited humanity as a whole.

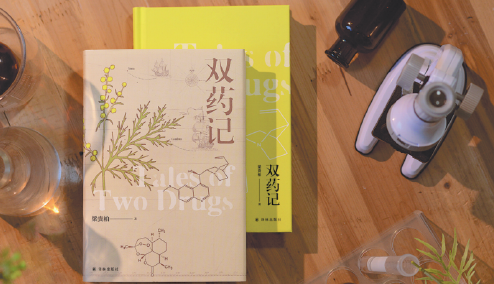

The question is why, during the more than 16 centuries since Ge, there had been no progress regarding the use of qinghao to treat malaria in China. That is something Liang Guibai, the author of Shuang Yao Ji, or A Tale of Two Drugs, hopes readers will think about while reading. He's co-founder and chief scientist at Shanghai-based SHEO Pharmaceuticals, and an independent consultant in preclinical research and development of drugs.

The "two drugs" in the title refer to quinine and artemisinin, two naturally occurring antimalarial drugs.

In concise and vivid language, Liang uses what he calls a mix of half fiction and half nonfiction to present key historical moments in scientific advancement.

The writer Han Songluo comments on the book that besides science, it focuses on the history of the two drugs and also explores the related history of human migration, transportation, medicine, warfare, territorial change, political games, technological advancements, and even monetary history.

Liang did a lot of research before writing to find details of those key moments. Where the records were missing, he devised stories to make the book "more visually engaging".One example is the aforementioned story of Ge prescribing medicine to save people at the foot of Luofu Mountain.

About eight years ago, Liang, a drug research and development scientist with a doctoral degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the United States, was invited to give 12-hour lectures on new drug developments at a business school.

Twelve hours is a long time, so he incorporated a lot of background information about the new drug development process into the lectures, including the tale of the two drugs.

After hearing him, one of Liang's friends said that he should write a book based on the lectures. Liang wrote an outline and proposed it to Yilin Press, with which he was already working on the book series, The Stories of New Drugs.

"I feel I am the right person to write the book, not only because I have gathered so much background material of the two drugs, but also because of my personal experience," he says.

The discovery of quinine and artemisinin, two natural medicines, fundamentally changed human health, altered the world order, and profoundly transformed the worlds of chemistry students like Liang.

When he was studying chemistry at Fudan University in the 1980s, Liang wanted to become a writer. As a young man interested in literature and art, he spent most of his time playing sports, reading world classics, playing cards and dancing, leaving him little time for chemistry. But the trajectory of his life was completely changed in a single lesson, during which the professor recounted the story of how quinine was synthesized, the starting point of modern organic synthesis.

If, as Liang wrote in the epilogue of his book, the synthesis of quinine "opened up the world of chemistry" for him and made him "truly fall in love with organic chemistry", then the synthesis of artemisinin allowed him to "start thinking about the magical world of life".

The peculiarity of qinghao urged him to think deeper: "Why does sweet wormwood contain a compound with such a unique structure? Why is it only found in that plant, and not in others like grass? Is it truly meant to be a natural compound for killing malaria parasites?"

These questions, he explains, may also be helpful in inspiring people to think about how to find the next "artemisinin" hidden in the compendium of TCM prescriptions.

"If there is an initial intent in writing the book, it is to get people to think about this question together. Right now, it's a question without an answer. But if more people start thinking about it, we might be able to find the answer, or answers, so that we won't wait another 1,600 years to find the next 'artemisinin'," he writes.

The book includes excerpts about sweet wormwood and treatment methods for malaria from the Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang and Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) medical expert Li Shizhen's Compendium of Materia Medica for reference.

"Compared to Li's encyclopedic collection of herbs and prescriptions, I'm more interested in Ge's 43 prescriptions for treating malaria, because among the three known effective natural antimalarials — quinine, artemisinin and the alkaloid of the antifebrile dichroa root, he got two correct more than 1,600 years ago," he says.

"Compared to sweet wormwood, obviously Ge had conducted more studies on dichroa root, and had been trying to improve the prescription for it," he says.

Despite the plentiful sorcerous content in the Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang, Liang says that he will continue researching Ge's prescriptions to see if there are any other special discoveries.

CHINA DAILY

<figcaption>Left: Shuang Yao Ji, or A Tale of Two Drugs, reveals scientific milestones regarding quinine and artemisinin, both antimalarial drugs. Right: Liang, the author, is a drug research and development scientist.</figcaption></figure>

Today's Top News

- SCO summit poised for fruitful outcomes

- Steps to spur consumption, enhance vitality

- Flag patterns for four branches of PLA unveiled

- China seeks to deepen dialogue, consultations with US

- Pacific Ocean should not be turned into a sea of zero-sum disturbances: China Daily editorial

- Xi signs order to commend military units, individuals