Biography traces a soldier's journey from captive to comrade

YAN'AN, Shaanxi — As a child, Yokichi Kobayashi devoured Chinese novels about the war against Japanese aggression and wondered why some captured soldiers later helped their former enemy. The answer came through his father's story.

Over the past 50 years, he meticulously pieced together the life of his father, Kiyoshi Kobayashi, eventually chronicling it in a biography. This year, which marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), the 74-year-old Japanese authorized a Chinese website to publish the book.

"As a Japanese, I ultimately chose to fight alongside the Chinese during the war of resistance because the Communist Party of China helped me realize the injustice of Japan's war of invasion," Kiyoshi once told his son.

The Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school reeducated many Japanese captives, transforming their perspectives, says Yokichi. "Many of them later joined the fight against Japanese fascism, playing a crucial role in the broader anti-fascist struggle."

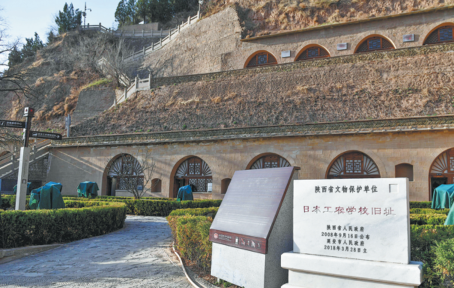

The school opened in May 1941 on Baota Mountain with just 11 students. By August 1945, enrollment had grown to more than 300. Over 30 cave dwellings served as dormitories, classrooms, and other facilities, some of which remain well-preserved and attract visitors today.

Li Donglang, a professor with the Party School of the CPC Central Committee (National Academy of Governance), says, "The school aimed to transform the mindset of Japanese prisoners. It reflects the Party's effectiveness in weakening enemy forces and highlights the importance of military-political work."

Kiyoshi was born into a businessman's family in Osaka. In 1938, at the age of 20, he was enlisted and sent to China the following year. In 1940, he was wounded in a battle against the Eighth Route Army and captured.

"At first, my dad tried to escape and even considered killing the Chinese army leaders," Yokichi says. "He even helped another Japanese prisoner attempt to flee."

Kiyoshi, like many Japanese soldiers, had been told that Japan's actions were defensive and intended for regional peace.

But during his study in Yan'an, he realized that neither Chinese nor Japanese people wanted the war, which caused immense suffering on both sides. Kiyoshi recognized himself as a victim, torn from his family, and saw how Japanese warmongers underestimated China's strength and resolve.

At the site of the school, display boards recount this little-known history to visitors.

Information on the board shows students engaged in morning exercises, classes and discussions covering politics, economics, Japanese affairs, current events, philosophy, world geography, Chinese language and art.

Kiyoshi later told his son that what he had learned in Japan was mere propaganda; only through study in Yan'an did he understand class struggle and the exploitative nature of reactionary powers.

Data show that 53.8 percent of the students were workers, while the rest were farmers, shop assistants, businesspeople, and others. Most had been ordinary soldiers or low-ranking officers when captured.

In revolutionary bases like Yan'an, prisoners of war were treated well, a stark contrast to the practices of the German fascists and Japanese militarists during the war.

A 1943 menu shows students had meat daily. The Great Production campaign ensured adequate food and clothing. Yokichi recalls his father learning to make dumplings with Chinese comrades, often overstuffing the wrappers at first, but gradually mastering the skill.

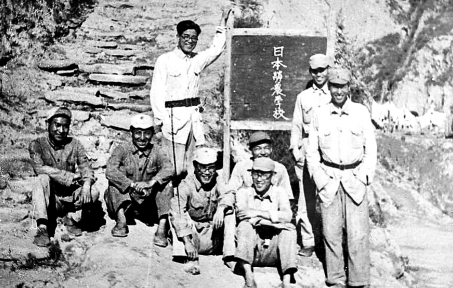

Outside the classroom, students made their own chess, mahjong and baseball equipment. Black-and-white photos show Japanese students performing alongside Chinese soldiers, dancing, and taking part in cultural activities.

After graduation, many former Japanese soldiers joined anti-war efforts. Some voluntarily enlisted in the Eighth Route Army, weakening enemy morale. In 1945, after Japan's surrender, Kiyoshi persuaded Japanese soldiers to lay down arms. Asked if he was Japanese, he replied, "Yes, I am. But I am now a member of the Eighth Route Army."

After the war, Kiyoshi stayed in China while most students returned to Japan, though many revisited the Yan'an caves in later decades.

Takashi Kagawa and five others returned in 1979. "I have always regarded Yan'an as my second hometown," he says. "It was there that hundreds of Japanese youths recognized the evil of aggression and joined hands with Chinese friends to end the war quickly. Many even sacrificed their lives." Nearly 50 members of the Japanese anti-war alliance died fighting Japanese troops.

"The United Front was a key tool the CPC used to defeat the enemy during the war," says Hao Xueting, former research office director of the Taihang Memorial Museum of the Eighth Route Army.

The caves have been preserved over decades, despite damage from heavy rain in 2013. Renovation began in 2015, and the site opened to the public in 2019.

Yokichi hopes to visit the place where his father lived and studied. Now head of a Japanese organization promoting friendly relations with China, he says, "I feel obliged to carry on my father's wish to cherish peace, oppose war, and help more people understand that the friendship between Japan and China was hard-won."

He adds, "Today, Japan needs to learn from its past. A country's self-reflection matters more than another's tolerance. Only nations that confront their mistakes can earn true respect."

Xinhua

Today's Top News

- China releases details of Huangyan Island nature reserve

- Xi congratulates president of Guyana on reelection

- Get the timing right to reduce 'debt cost' of natural disasters

- Advancing cooperation in global service trade urged

- PPI declines ease in Aug, first since Feb

- Xi: Grottoes are treasures of civilization