White elephant stomp

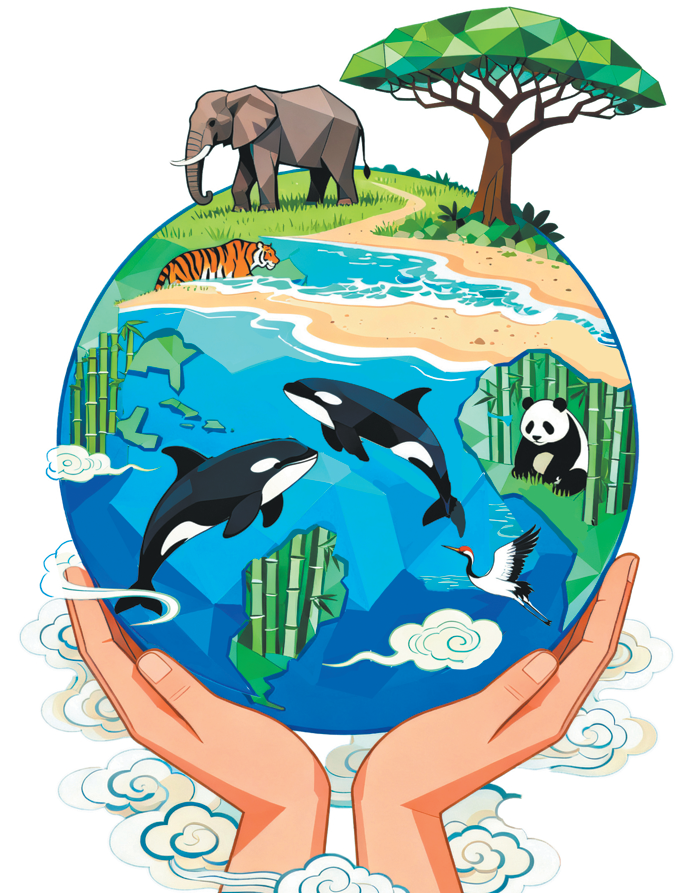

The China-US joint action on ivory has been a successful practice that should be extended to the protection of other endangered species

On Sept 25, 2015, at a joint press conference in Washington, Chinese President Xi Jinping and then US president Barack Obama jointly announced that the two countries would take "timely and decisive measures" to completely ban their domestic ivory markets.

This joint declaration not only marked a historic commitment by the world's two largest ivory-consuming nations, but also added a powerful chapter to global wildlife conservation. Looking back a decade later, we can see more clearly how this decision became a turning point for the protection of African elephants and advanced global anti-poaching and anti-wildlife trafficking efforts.

Around 2010, African elephants faced an unprecedented survival crisis. Studies show that in 2011 and 2012, about 22,000 and 25,000 elephants respectively were poached for ivory. In Central Africa, forest elephant populations fell by 62 percent in a decade, and their range shrank by 30 percent.

The root of this crisis lay in the global ivory market, especially demand from Asia and the West. Although China has banned the ivory market and established a registration and certification system for ivory products, the international coexistence of legal and illegal markets created loopholes that criminal networks exploited. The United States long remained the world's second-largest ivory consumer, due to loopholes in border control, antique ivory trade and enforcement challenges.

By 2015, the black-market industry chain of poaching and smuggling had become increasingly globalized, involving armed poaching gangs on African savannas, transnational smuggling syndicates and retailers in consumer nations, forming a $20 billion branch of the illegal wildlife trade. Against this backdrop, the joint China-US ivory ban was not only an environmental necessity but also a demonstration of great-power responsibility.

In September 2015, President Xi and president Obama announced the decision to comprehensively ban domestic ivory markets in both countries. China released a timeline in 2016 and fully closed ivory carving factories and retail outlets by the end of 2017, shutting down 172 licensed facilities. The US revised the Endangered Species Act and implemented a nearly complete ban on ivory imports, exports and interstate trade. After the ban was announced, the international community widely praised the action as "a key step in saving elephants".Other markets soon tightened their controls as well. The European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada and Singapore also introduced stricter regulations.

According to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE) Program's monitoring of PIKE (calculated as the number of illegally killed elephants found divided by the total number of elephant carcasses encountered), from 2003 to 2023, ivory poaching surged after the one-off legal ivory sale in 2008 and peaked in 2011. However, after the 2015 China-US ban announcement, PIKE dropped significantly, from around 69.1 percent to 38.8 percent, and continued trending downward. Meanwhile, ivory product prices in China fell sharply after the ban, and consumer interest waned.

Surveys between 2017 and 2021 showed that more Chinese consumers lost interest in ivory purchases, with demand reaching historic lows. While some black markets persist, their scale has contracted considerably. The ban relied not only on the law but also on enforcement and awareness campaigns.

China repeatedly destroyed confiscated ivory to signal zero tolerance, while the US strengthened both state and federal enforcement to close loopholes in antique ivory. Public education shifted ivory's image from a "luxury good" to an "illegal good", fundamentally changing social perceptions.

Despite positive impacts, challenges remain. Studies show that underground markets and cross-border smuggling still exist in some Southeast Asian countries. Due to weak governance, poaching, though reduced, has not disappeared in parts of Africa. Corruption, weak law enforcement and human-elephant conflict remain serious threats.

Sustainable alternatives for local communities in elephant range countries are critical. Protection cannot rely solely on enforcement — it must also provide livelihood options. Only by enabling communities to benefit from eco-tourism, compensation schemes and conservation-linked income can poaching incentives be reduced. Without such measures, bans risk shifting the burden onto already poor communities.

The past decade of the ivory trade ban demonstrates that shutting down domestic markets is essential to cut demand, and that enforcement and public education must go hand in hand. The China-US joint declaration set a powerful precedent, encouraging other countries to follow and showing that international cooperation is indispensable.

Looking forward, China and the US can build on this legacy by deepening cooperation in several strategic areas.

First, they can strengthen joint enforcement and intelligence sharing, drawing on past successes such as Operation COBRA III, a multinational crackdown jointly organized by China, the US and partner countries across Asia, Africa and North America to combat wildlife crime in 2015. Building on such precedents, the two nations can dismantle trafficking networks more effectively.

Second, both sides can apply digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain and big-data platforms, to improve the traceability of wildlife products and strengthen online monitoring of illegal markets.

Third, they can expand public awareness campaigns, reinforcing the shift from ivory as a luxury good to an illicit good.

At the same time, the two countries should support African communities, ensuring that conservation brings tangible economic benefits through eco-tourism and alternative livelihoods. Cooperation can extend beyond protecting elephants to other species, such as pangolins, rhinos and marine wildlife.

Finally, China and the US can lead together in multilateral fora such as CITES and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, championing stronger global biodiversity governance.

Although many official channels of environmental cooperation between China and the US have stalled, there remains significant room for engagement under the UN framework. For instance, both countries could jointly support the UN Environment Programme's environmental early warning programs and encourage civil society collaboration in the CITES, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the UNFCCC processes. Such efforts would sustain dialogue, bridge gaps and maintain momentum in global conservation even amid broader political tensions.

These measures would not only consolidate the legacy of the ivory trade ban but also reflect President Xi's vision of an ecological civilization and shared responsibility. The evidence is clear: cooperation delivers more than confrontation does.

If China and the US continue to work side by side, they can safeguard elephants and provide solutions for wider global environmental crises, from biodiversity loss to climate change. The ivory ban is a milestone victory, but it is also a new beginning.

The author is a professor of ecology at the Beijing Normal University. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.