Of rivers and passing clouds

By Yang Guang (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-07-09 09:38

|

Large Medium Small |

Wan's latest novel Paper Restaurant is released in the year that marks the 100th anniversary of her famous father's birth. Yang Guang reports

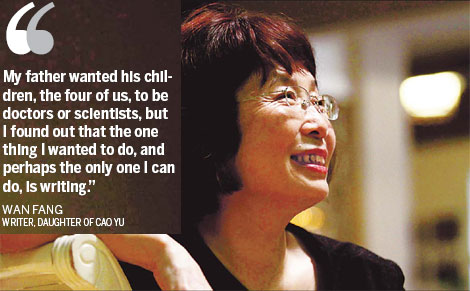

A novelist and playwright in her own right, Wan Fang's name is usually associated with her father Cao Yu (1910-96, originally named Wan Jiabao), the "Shakespeare of Chinese literature" and founder of modern Chinese theater.

Eight years since her last novel, Wan's latest, Paper Restaurant (Zhi Fanguan), is released in the year that marks the 100th anniversary of her father's birth.

According to Wan, the story spanning the Tangshan earthquake in 1976 and the 2008 Beijing Olympics has brewed over many years.

Protagonists Tu Gang and You Ling are disparate, most prominently in their attitudes toward life: Tu drifts with the tide of life, while You squeezes the very last drop of its blood. But they end up being together, after all the twists and turns life has to offer.

"Men are like rivers, running from different sources but converging into the same river bed in the end," the 58-year-old Beijing native says.

"However different, they arrive at the same destination. I am not yet able to specify it, but I have tried to invest my understanding into the novel."

She names it in the same vein with her earlier "empty trilogy" (Empty Mirror, Empty House and Empty Lane), all centering on discussions about love and marriage. The paradoxical combination - the abstract and metaphysical with the concrete and real - embodies Wan's understanding of life.

"My conclusion is that life is transient and obscure. It is usually the case that in retrospect, we suddenly realize we have spent our lives in sort of chaos - a sense of emptiness."

"In the meantime, nevertheless, empty is full, in ancient Chinese philosophy."

This is perhaps how and why she conjures the axiomatic, despite somewhat cynical, motif of the novel: "Whatever it is, if it is not in your mind, then it is nothing."

Wan deems life as a process of compromise. "When young, one always confronts life head on; but with the passage of time, one gradually realizes that one has no other option but to accept life as it is."

Wan started writing under the influence of her father, but became a writer against his wish.

"My father wanted his children, the four of us, to be doctors or scientists," she explains, "but I found out that the one thing I wanted to do, and perhaps the only one I can do, is writing."

During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), she was sent to the countryside in Northeast China's Jilin province. At 24, she returned to Beijing, first working as an editor and then a playwright at the Central Opera Theater.

For her, there are two kinds of writers - one is born; the other is nurtured. Her father, who wrote his magnum opus Thunderstorm (Leiyu) at the age of 23, belongs to the former, while she falls in the latter. It was not until the early 1990s, when she published the novella Murder (Sharen) in the prestigious literary journal Harvest that she was sure she could live by her pen.

"Writing is hard work. It still stings me, when I recall how my father suffered from being desperately willing, but unable to produce anything satisfactory in his late years."

"One night he called me to his room, urging me to force him to write," she recalls, "he kept muttering 'I don't want to live like this anymore. I want to write a big thing before I die'."

Most of Cao's well-known works, including Thunderstorm (1933), Sunrise (Richu, 1936), The Wilderness (Yuanye, 1937), and Peking Man (Beijing Ren, 1940), were created before the founding of New China in 1949. The mental tortures inflicted upon him during the "cultural revolution" prevented, and the various official posts he held distracted him, from serious literary creation. His last work Wang Zhaojun was produced in 1979.

"But he was genuinely fond of writing," Wan says and recalls how her father buried himself in writing in the broiling summer, at times pacing around his study and reading the lines to himself.

He once wrote: "I hold an absurd theory, that a soldier should die in the battle field, an actor on the stage, and a writer at the desk A man should strain every nerve before he dies, or he will feel his life is wasted."

Wan adapted Sunrise into a film and The Wilderness into an opera in the 1980s. "Given my father's achievements, I dared not touch the theater until after 50," she admits.

Her first original script There Is a Poison (You Yizhong Duyao) won the national Cao Yu Drama Award in 2008. "When holding the trophy inscribed with his portrait, I felt I could talk to him," she says, "I told him, 'Dad, you should be proud of me'."

Now the torch has been passed on to the third generation. Director Su Peng, Wan's son, has staged There Is a Poison again this year to commemorate his grandfather.