The DNA behind Darwin's pigeons

Updated: 2013-02-17 08:37

By Carl Zimmer(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

DNA yields clues to pigeons' diversity. A Jacobin. Richard Bailey |

|

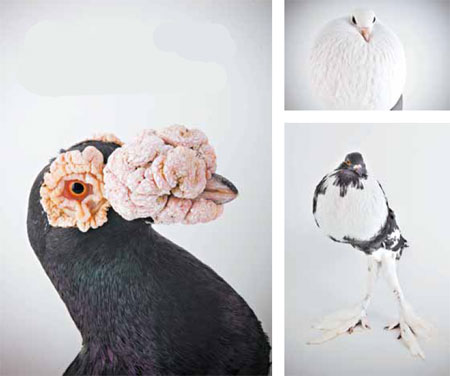

Scientists studied the head crests of pigeons. From top: a Horseman Pouter, Pygmy Pouter and English Carrier. Photographs by Robert Clark / Institute |

In 1855, Charles Darwin started raising pigeons. In the garden of his country estate, Darwin built a dovecote. He filled it with birds he bought in London from pigeon breeders. He favored the fanciest breeds - pouters, carriers, barbs, fantails, short-faced tumblers and many more.

"The diversity of the breeds is something astonishing," he wrote later in "On the Origin of Species" - a work greatly informed by his experiments with the birds.

Pigeon breeding, Darwin argued, was an analogy for what happened in the wild. Nature played the part of the fancier, selecting which individuals would be able to reproduce. Natural selection might work more slowly than human breeders, but it had far more time to produce the diversity of life around us.

Later generations of biologists shifted their attention to other species, like fruit flies and E. coli. But now Michael D. Shapiro, a biologist at the University of Utah, is returning pigeons to the spotlight.

In a recent article published online by the journal Science, an international team of scientists led by Dr. Shapiro reports that it has delved into a source of information Darwin didn't know about: the pigeon genome. So far, they have sequenced the DNA of 40 breeds, seeking to pinpoint the mutations that produced their different forms.

Their work supports Darwin's original claim that all pigeon breeds descend from the rock pigeon, whose range stretched from Europe to North Africa and east into Asia.

Archaeologists have speculated that rock pigeons flocked to the first farms in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East, where they pecked at loose grain. Farmers then domesticated them for food. Later, humans bred the birds to carry messages. By the eighth century B.C., Greeks were using pigeons to deliver the results of Olympic Games.

Eventually, people began breeding pigeons for pleasure. Akbar the Great, a 16th-century Mughal emperor, traveled with his colony of 10,000 pigeons. He bred some for their ability to tumble through the air, and others for their extravagant beauty.

Dr. Shapiro and his colleagues have worked out the genealogy of these breeds. They found, for example, that fantail pigeons, one of Akbar's favorite breeds, are closely related to breeds from Iran. Dr. Shapiro suspects that their kinship is a result of trade along the Silk Route between the Mughal Empire and Persia.

Some of these breeds would escape from their owners and mate with wild rock pigeons. As a result, Dr. Shapiro's team has struggled to find a pigeon with "pure" rock pigeon DNA.

European colonists brought their domesticated pigeons to the New World, where they raised them for food, messages and diversion.

Dr. Shapiro set out to discover what Darwin could not: the genetic basis of the birds' evolution. He picked an extravagant trait to study: head crests.

"Some birds just have just a little peak, some have what looks like an inverted shell, some have a mane, and some have their entire head engulfed in feathers," he said.

The team found that the closest relatives of crested breeds are uncrested breeds. In other words, pigeon breeders produced crests on the birds on five separate occasions. The team also found that all of the crested breeds shared the same mutation in the gene EphB2.

Bird embryos develop placodes, disks of tissue on their skin from which feathers will grow. The scientists found that in pigeons without crests, EphB2 became active on the bottom edge of the placodes; in crested pigeons it was active on the top.

The experiment suggests that EphB2 tells the placode which way is up. In most pigeons, it instructs the feathers to grow down the neck; but the mutation changes the location where EphB2 switches on, effectively turning the feathers upside down and producing a crest.

The new research suggests that the crested version of EphB2 mutated only once.

Dr. Shapiro found that it takes two copies of the mutant gene to reverse the feathers. When the mutation arose, it was passed down invisibly from pigeon to pigeon. Only when two carriers happened to mate did they suddenly produce a crested chick.

Dr. Shapiro is studying other traits to see if this pattern holds. "The more examples that we have," he said, "the more we can understand what the general trends in evolutionary change are."

The New York Times

(China Daily 02/17/2013 page9)