Scientists track microbes of the great indoors

Updated: 2013-06-09 05:48

By Peter Andrey Smith(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

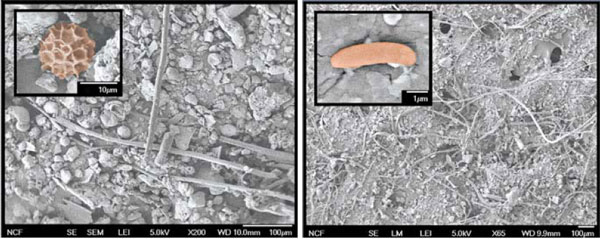

Researchers are swabbing surfaces inside homes and hospitals to discover how people "colonize" spaces with microbes. A fungal spore, far left, and bacterium from a door. Noah Fierer |

BOULDER, Colorado - Two blocks east of a strip mall in Longmont, one of the world's last underexplored ecosystems came into view: a sandstone-colored ranch house, code-named Q.

Noah Fierer, 39, a microbiologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and self-described "natural historian of cooties," walked in, joining researchers inside. One swabbed surfaces with sterile cotton swabs. Others logged the findings from two humming air samplers: clothing fibers, dog hair, skin flakes, particulate matter and microbial life.

Ecologists like Dr. Fierer have begun peering into an intimate, overlooked world that barely existed 100,000 years ago: the great indoors. They want to know what lives with us and how we "colonize" spaces with viruses, bacteria, microbes. Homes, they've found, contain identifiable ecological signatures of their human inhabitants. Even dogs exert a significant influence on the tiny life-forms living on our pillows and television screens.

Once ecologists have more thoroughly identified indoor species, they hope to come up with strategies to manage homes, by eliminating harmful species and fostering those beneficial to health.

But the first step is simply to take a census of what's already living with us, said Dr. Fierer; only then can scientists start making sense of their effects. "We need to know what's out there first. If you don't know that, you're wandering blind in the wilderness."

Besides the charismatic fauna commonly observed in North American homes - dogs, cats, fish - ants and roaches, crickets and carpet bugs, mites and millions upon millions of microbes, including hundreds of multicellular species and thousands of unicellular species, also thrive in them.

Dr. Fierer has teamed up with Rob Dunn, a biologist at North Carolina State University, to sample the microbial wildlife in 1,400 homes across the United States. The project - known as The Wild Life of Our Home - relies on volunteers who swab pillowcases and cutting boards, then send in samples for analysis.

"For the entire history of humanity, we have created environments around us, in our daily lives, in a very unintentional way. The control that we've exerted is predominantly one in which we kill the ones that might be bad," Dr. Dunn said. "That's saved a lot of lives. It's also favored this whole suite of species that we know very, very little about."

Take an average kitchen. In a study published in the journal Environmental Microbiology, Dr. Fierer's lab examined 82 surfaces in four Boulder kitchens. Bacterial species associated with human skin, like Staphylococcaceae or Corynebacteriaceae, predominated. Evidence of soil showed up and species associated with raw produce appeared. Microbes - including sphingomonads, some strains infamous for their ability to survive in the most toxic sites - splashed in a kind of jungle above the faucet. Dr. Fierer's lab also found a few potential pathogens, like Campylobacter, lurking on the cupboards.

Most of the inhabitants are relatively benign. In any event, eradicating them is neither possible nor desirable.

In the team's first study of 40 homes in North Carolina, published in the journal PLoS One, they found that humans leave bacteria by touching surfaces with exposed skin, and at room temperature, a healthy human kicks up a "convective plume" of about 37 million bacteria per minute that disperse throughout the home and can survive for extended periods.

The effort to catalog the creatures of the great indoors began in earnest in 2004, when Paula J. Olsiewski, a program director at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation in New York, sent out a call to examine buildings as a first line of defense against bioterrorism. The foundation has put up $28 million for projects, including one, the Hospital Microbiome Project, that involves swabbing patients' noses, armpits, hands and feces, as well as newly constructed nursing stations and 10 patient rooms - a total of 12,000 swabs.

The yearlong investigation will tackle a pressing concern: One in every 20 patients acquires infections in a hospital, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in America.

Another study, published in 2012 in The ISME Journal, found that hospital patients were more likely to encounter pathogens in mechanically ventilated rooms than in ones with access to fresh air from outside.

"Right now, we don't understand how buildings work" as ecosystems, said Jordan Peccia, an environmental engineer at Yale University in Connecticut.

He added: "We've seen it as an improvement to make homes more insulated, but maybe that's a mistake from the standpoint of ecological diversity."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/09/2013 page11)