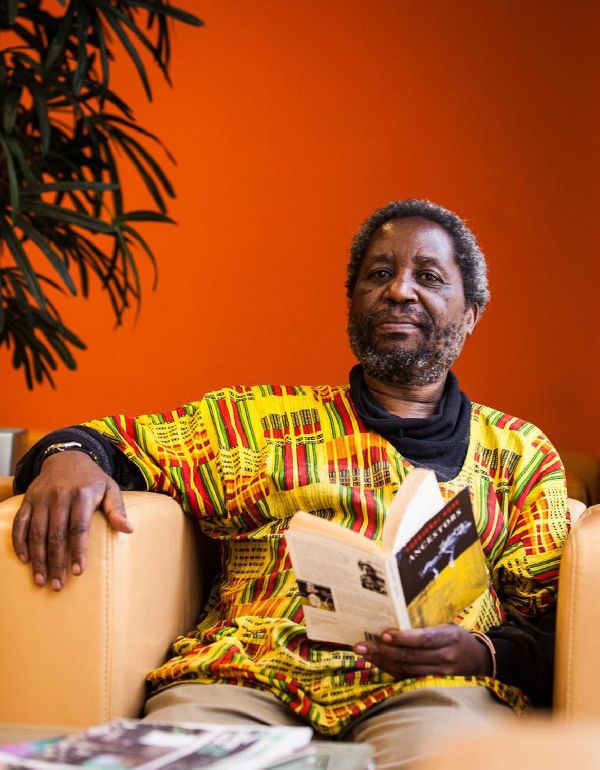

The death in Norway last month of Zimbabwe writer and activist Chenjerai Hove rocked the African literary world. Hove, who was 59, went into exile in 2001. He had been a critic of the government of President Robert Mugabe. Fellow writers and readers agree Hove combined masterful literary technique with patriotism and a passion for justice.

Chenjerai Hove was born to a village chief in rural Rhodesia in 1956.He was deeply horrified by the violence he witnessed during the 13-year war for independence against Britain that ended in 1980.

“Bones,” his most celebrated novel, chronicles a mother’s desperate search for her son, who disappeared after joining the guerilla struggle. The 1988 novel garnered him the prestigious “Noma” prize and other honors.

Jack Mapanje, a fellow Zimbabwean poet and refugee, was Hove’s longtime friend. He says pre-independence writers usually wrote in European literary styles. But “Bones” reveled in the rural rhythms and imagery of Hove’s native Shona language to tell a homegrown tale.

“He was deeply involved [in] the African culture, the dance, the music, the drums and so on. But [was] also steeped in the oral tradition, the folktales, the proverbs, and all this. He loved that. We have lost a writer who was steeped in African traditions to tell his story about the world,” he said.

It was a story that often intertwined hope with disappointment and sorrow. Mapanje says it broke Hove’s heart to witness, what he saw as the brutality of British rule continue in an independent Zimbabwe.

Mapanje said, “He loved the people. He loved the masses and he did not like anybody who exploited the ordinary person – so colonialism as well as the government of Mugabe. And that became part of this main theme that runs through his poetry, short stories as well as the novel itself.”

The universal struggle for justice is a constant theme throughout Hove’s four volumes of poetry, which include “Red Hills of Home” and “Rainbows in the Dust.” In 2001, Hove recited his poem “Dispute” at an international festival in Medellin, Colombia.

“The strength of the republic is not measured in unmarked cars or guns or poisons or disappearances. The strength of the republic is measured in beggars’ arms, the dreams of the poor, the waste of the rich. The strength of the republic is measured in ants, not elephants in the park…”

Hove helped to found and head the Zimbabwe Writers Union, a group of dissidents that gathered in Harare’s cafes. His criticism of government repression was met with death threats and other intimidation tactics. In 2001, Hove was forced into exile, without his family. He first went to France and then to the United States, where he was offered writers’ fellowships at Brown University and elsewhere.

He finally settled in Stavanger, Norway, where he was given refuge by the International Cities of Refuge Network or ICORN. The organization shelters writers and artists at risk and promotes freedom of expression.

ICORN Director Helge Lunde knew Hove well. He said Hove was not able to complete any novels in exile.

“It was not possible for him to continue exactly as before. Of course he continued to write poetry and short stories. But he also wrote drama and a lot of journalism and a lot of non-fiction. He was translating King Lear into Shona.. We will need some time to grasp the real significance of Chenjerai’s work, both as a writer-poet and as a freedom fighter, but I am very sure that his work will live on.”

Before his sudden death on July 12th, apparently from liver disease, he was working on a major book about writers in exile and the toll it had taken on them. Chenjerai Hove’s body was flown back to Zimbabwe for burial.

It’s clear that Hove continued to acutely feel the loss of his homeland. He wrote about this, saying, “In my long journey home, I will search for the voices that gave me the many colors of imagination and listen to the songs of the birds and rivers of my land. Nothing can take away this deep echo of desire from me.”

The death in Norway last month of Zimbabwe writer and activist Chenjerai Hove rocked the African literary world. Hove, who was 59, went into exile in 2001. He had been a critic of the government of President Robert Mugabe. Fellow writers and readers agree Hove combined masterful literary technique with patriotism and a passion for justice.

Chenjerai Hove was born to a village chief in rural Rhodesia in 1956.He was deeply horrified by the violence he witnessed during the 13-year war for independence against Britain that ended in 1980.

“Bones,” his most celebrated novel, chronicles a mother’s desperate search for her son, who disappeared after joining the guerilla struggle. The 1988 novel garnered him the prestigious “Noma” prize and other honors.

Jack Mapanje, a fellow Zimbabwean poet and refugee, was Hove’s longtime friend. He says pre-independence writers usually wrote in European literary styles. But “Bones” reveled in the rural rhythms and imagery of Hove’s native Shona language to tell a homegrown tale.

“He was deeply involved [in] the African culture, the dance, the music, the drums and so on. But [was] also steeped in the oral tradition, the folktales, the proverbs, and all this. He loved that. We have lost a writer who was steeped in African traditions to tell his story about the world,” he said.

It was a story that often intertwined hope with disappointment and sorrow. Mapanje says it broke Hove’s heart to witness, what he saw as the brutality of British rule continue in an independent Zimbabwe.

Mapanje said, “He loved the people. He loved the masses and he did not like anybody who exploited the ordinary person – so colonialism as well as the government of Mugabe. And that became part of this main theme that runs through his poetry, short stories as well as the novel itself.”

The universal struggle for justice is a constant theme throughout Hove’s four volumes of poetry, which include “Red Hills of Home” and “Rainbows in the Dust.” In 2001, Hove recited his poem “Dispute” at an international festival in Medellin, Colombia.

“The strength of the republic is not measured in unmarked cars or guns or poisons or disappearances. The strength of the republic is measured in beggars’ arms, the dreams of the poor, the waste of the rich. The strength of the republic is measured in ants, not elephants in the park…”

Hove helped to found and head the Zimbabwe Writers Union, a group of dissidents that gathered in Harare’s cafes. His criticism of government repression was met with death threats and other intimidation tactics. In 2001, Hove was forced into exile, without his family. He first went to France and then to the United States, where he was offered writers’ fellowships at Brown University and elsewhere.

He finally settled in Stavanger, Norway, where he was given refuge by the International Cities of Refuge Network or ICORN. The organization shelters writers and artists at risk and promotes freedom of expression.

ICORN Director Helge Lunde knew Hove well. He said Hove was not able to complete any novels in exile.

“It was not possible for him to continue exactly as before. Of course he continued to write poetry and short stories. But he also wrote drama and a lot of journalism and a lot of non-fiction. He was translating King Lear into Shona.. We will need some time to grasp the real significance of Chenjerai’s work, both as a writer-poet and as a freedom fighter, but I am very sure that his work will live on.”

Before his sudden death on July 12th, apparently from liver disease, he was working on a major book about writers in exile and the toll it had taken on them. Chenjerai Hove’s body was flown back to Zimbabwe for burial.

It’s clear that Hove continued to acutely feel the loss of his homeland. He wrote about this, saying, “In my long journey home, I will search for the voices that gave me the many colors of imagination and listen to the songs of the birds and rivers of my land. Nothing can take away this deep echo of desire from me.”

來源:VOA

編輯:劉明

上一篇 : Americans' Anger Grows Over Killing of Lion

下一篇 :

關注和訂閱

電話:8610-84883645

傳真:8610-84883500

Email: languagetips@chinadaily.com.cn